Forty years ago, on April 30 at 7:53 in the morning, the Marine helicopter Swift 2-2 departed from the United States embassy in Saigon, capital of South Vietnam. The helicopter carried the last batch of soldiers who had been waging a brutal, protracted war against the revolutionary peasant uprising of Hồ Chí Minh’s Việt Cộng guerrillas. Two and a half hours after the departure of Swift 2-2, the U.S. puppet regime in South Vietnam formally surrendered to Hồ. By the afternoon, Ho announced that the South Vietnamese government was “completely dissolved at all levels”. The Vietnam War was over.

Vietnam was the first time in history that the United States lost a war. A country armed to the teeth with the latest in modern weaponry which had marched to victory in two world wars found itself stopped in its tracks against a poor, colonized peasant nation struggling for freedom. The U.S. military was faced with a different kind of enemy: the popular resistance of the Vietnamese workers and peasants, a rising tide of social struggles at home, and increasing dissatisfaction within its own army. As the socialist historian Howard Zinn put it, “it was organized modern technology versus organized human beings, and the human beings won”.

The story of how the humans won is highly relevant today as we face a ruling elite that has carried out a policy of constant foreign wars for 14 years while attacking democratic rights at home and concentrating unimaginable wealth in its hands. If ordinary people stood up and stopped the war machine 40 years ago, we can build a mass movement to end the rule of the billionaires in our time.

A History of Resistance

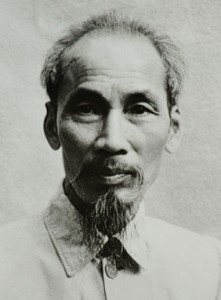

For over a century, the history of Vietnam was one of colonial conquest and anti-colonial resistance. Between 1859 and 1885, the French government instigated a series of military conquests in Southeast Asia, eventually establishing the colony of French Indochina in what is now Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. France ruthlessly exploited its colony through an oppressive plantation system. By World War II, the rising imperial power of Japan briefly drove out the French and established an even more ruthless colonial rule. It was during this time that Hồ Chí Minh, founder of the Communist Party of Indochina, formed the Việt Minh, an alliance with nationalist forces against Japanese rule.

Hồ became a socialist while living in France in 1921 and, inspired by the Russian Revolution, he joined the communist movement. But by the time Hồ came to prominence in the Vietnamese anti-colonial movement, the Russian Revolution had degenerated and the Soviet Union was under the bureaucratic dictatorship of Joseph Stalin. Capitalism remained abolished and real social gains were achieved. but the political power was taken away from working class people and concentrated in the hands of a privileged, parasitic caste at the top of society.

Hồ adopted Stalin’s bureaucratic, brutal and dictatorial methods, and embraced his political turn away from working class internationalism. Hồ followed the Stalinist advice to subordinate workers’ struggles to a nationalist alliance with “progressive” capitalists.

But there was also a genuine revolutionary socialist movement developing in Vietnam, lead by Tạ Thu Thâu, which supported Leon Trotsky’s fight against Stalinism and called for the working class to lead the struggle against colonialism. The Vietnamese Trotskyists established a powerful base among the workers of Saigon. When the Japanese were driven out of Indochina in 1945, the Trotskyists played a prominent role in a general strike in Saigon against the return of French rule. But Hồ’s Stalinists, at this point, looked to British, French, and American imperialism as a “progressive” ally against Japan. After the general strike, the Việt Minh, the fighters for independence under Hồ’s leadership, had the Trotskyists slaughtered and facilitated the return of French rule.

While Hồ Chí Minh saw French imperialism as an ally facilitating independence, French imperialism didn’t see things that way. As France re-established its colonial rule, the Việt Minh was pushed to the left by the force of events and waged a guerrilla struggle against French rule. This culminated in the battle of Điện Biên Phủ in 1954, which forced out the French and established Hồ’s rule in North Vietnam. Hồ’s regime overthrew capitalism and launched a massive land reform program that vastly improved the standard of living for the majority of the population. But, politically, North Vietnam was a bureaucratic dictatorship made in the Soviet Union’s image. Nevertheless, given the nightmare of capitalist stagnation and poverty in the colonial and neo-colonial world, it is understandable that the Vietnamese Revolution was enormously attractive to millions of people around the world.

In South Vietnam, however, an entirely different regime was established. The U.S. emerged from World War II as the world’s biggest superpower, with the Soviet Union as its biggest rival. Despite the willingness of the Stalinists to cut deals with the U.S. and other imperialist powers, the U.S. ruling elite feared the spread of further revolutionary upheavals. In particular they believed that a Việt Minh victory would lead to a “domino effect” with more countries leaving the sphere of capitalism across Southeast Asia. The U.S. therefore propped up the corrupt and repressive South Vietnamese puppet dictator Ngô Đình Diệm. This regime had nothing to do with democracy, independence or self-determination.

In response, the Việt Cộng guerrilla movement was formed, backed by North Vietnam and, in 1959, a new guerrilla war was launched against the South Vietnamese regime.

American War Drive

Ostensibly, the Vietnam War was not a war at all, but a “police action”. The process began under Eisenhower, who secretly sent military advisers to South Vietnam. Under Kennedy, the number of secret advisers rose to sixteen thousand. But it was Kennedy’s successor Johnson who, under the guise of the manufactured “Gulf of Tonkin incident” in 1964, stepped up the intervention into a full-scale war.

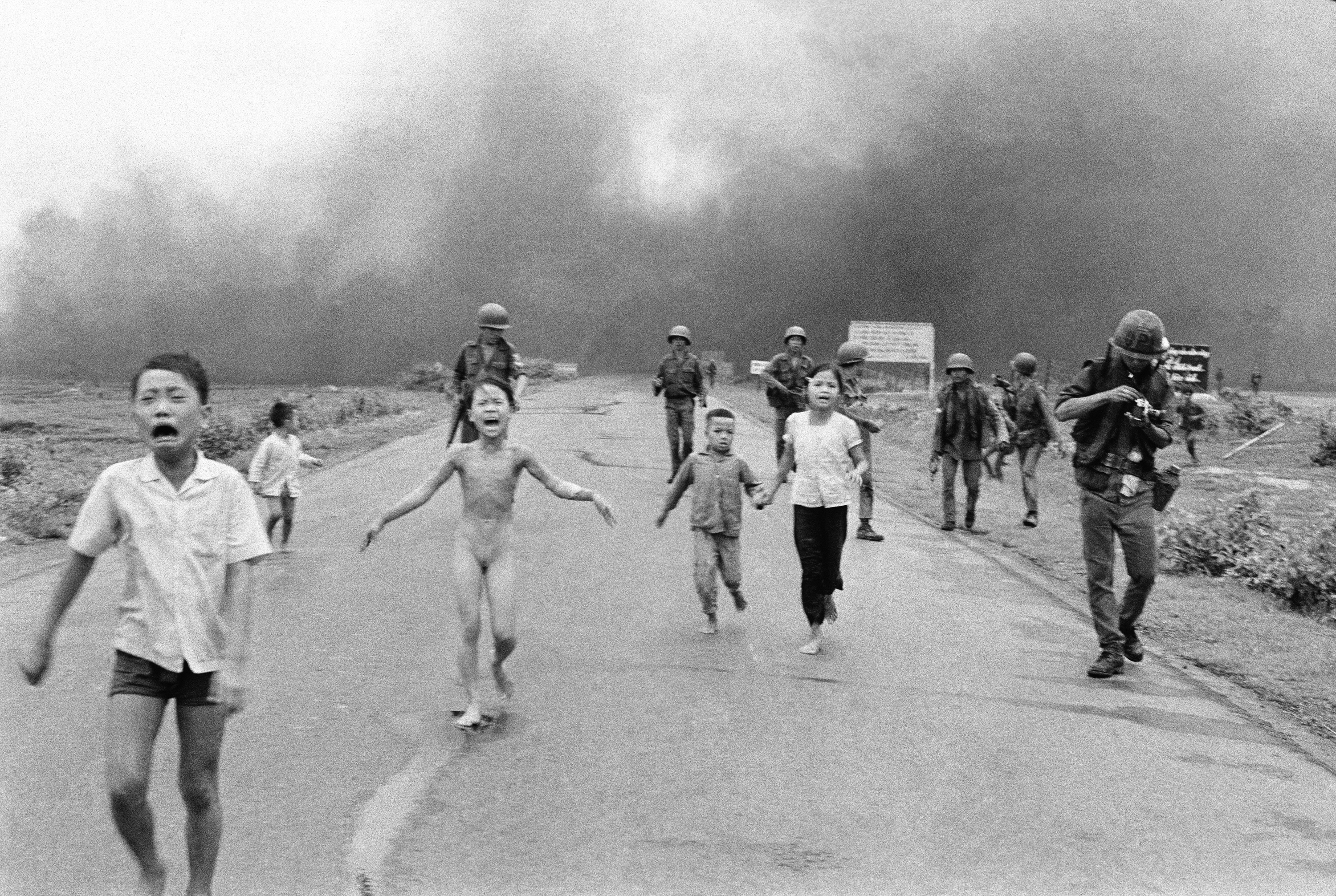

The scale of the war was massive. A total of 2.7 million American soldiers served in the war, representing 9.7% of their generation. Vietnam and its neighbors Laos and Cambodia were hit by 7 million tons of American bombs, more than twice the amount of bombs dropped on Europe and Asia in World War II. As part of Operation Ranch Hand, almost 20 million gallons of chemical herbicides were sprayed as well, including the notorious Agent Orange. This was part of a policy of “forced draft urbanization”, destroying the peasants’ crops to starve guerrillas out of the countryside. In addition, 338,000 tons of napalm bombs were dropped in the region, all to back and defend a hated dictatorial regime.

As the U.S. military effort became bogged down because of the mass opposition of the Vietnamese people, the brutality of the occupation inevitably increased. In one infamous incident, American troops entered the hamlet of My Lai on March 16, 1968, rounded up the inhabitants, children included. They were then ordered into a ditch, 500 in all, and methodically shot to death. The My Lai Massacre was only the most well-known incident of this sort. As Colonel David H. Hackworth put it, “There were hundreds of My Lais. You got your card punched by the numbers of bodies you counted.”

On January 31, 1968, the Việt Cộng launched the Tet Offensive, a military assault on over 100 cities in South Vietnam designed to provoke a national uprising. Although the US was able to militarily defeat the Tet Offensive, the war began to look increasingly like a quagmire. That year, Richard Nixon was elected on the slogan of “peace with honor”. Despite promising to wind down the war, he instead expanded it. The bombing campaign was expanded from Vietnam to the country’s neutral neighbors of Laos and Cambodia. But this simply took the US deeper into the quagmire. By the end of the war, 58,220 American soldiers had been killed, and over 150,000 wounded.

The War at Home

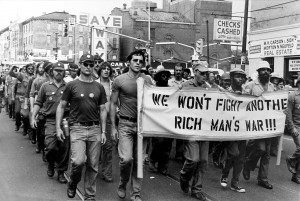

Ultimately, the United States was defeated because it was fighting a popular resistance. But it wasn’t just the resistance of the Vietnamese peasants, but also the massive anti-war movement in the U.S. itself. The movement began slowly in the early 1960s. Serious anti-war organizing first took place on university campuses, with groups like the Students for a Democratic Society holding anti-war teach-ins across the country and organizing demonstrations. Soon the movement would balloon into the biggest anti-war movement in U.S. history.

Establishment accounts of the anti-Vietnam war movement portray it as dominated by privileged students with the working class making up the “silent majority” that backed Nixon. However, this is a gross distortion of how consciousness actually developed. Due to the nature of the draft, the vast majority of soldiers were drawn from the ranks of the working class and oppressed. And they were the ones who witnessed the horrors of the war first hand. It’s true that conservative union leaders supported the war but this position faced internal dissent. By the end of the war opposition to the war was higher in the working class than the middle class and particularly strong among poor workers and African Americans.

The most significant working class resistance occurred within the army itself. A number of radical groups actively pursued a policy of entering the army to carry out anti-war activity among the soldiers. Other left-wing activists on the civilian side set up a network of coffeehouses, storefronts, and bookstores outside military bases, which became centers for dissent within the military. Anti-war GI papers flourished, with names like Fatigue Press, Harass the Brass, and The Star-Spangled Bummer. These organizing efforts helped bring the army into a state of disarray. In 1971, Marine Colonel Robert D. Heinl Jr. wrote:

“By every conceivable indicator, our army that remains in Vietnam is in a state approaching collapse, with individual units avoiding or having refused combat, murdering their officers and non-commissioned officers…Sedition, coupled with disaffection from within the ranks, and externally fomented with an audacity and intensity previously inconceivable, infest the Armed Services…”

This disintegration of the armed forces proved to be the final nail in the coffin and rendered the war unwinnable for the U.S.

Aftermath

It was the power of collective struggle, in the U.S. and Vietnam, that led to the defeat of U.S. imperialism. This had immediate consequences for the future of U.S. foreign policy. The draft was abolished and the military switched to an all-volunteer army. And an overall hostility to war among ordinary people led to “Vietnam Syndrome” where the U.S. government became unwilling to engage in direct warfare for fear of provoking immediate massive opposition.

But with the collapse of the Stalinist regimes in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, capitalism proclaimed itself triumphant. More slowly, Vietnam also headed towards the restoration of capitalism. Globally, the workers’ movement went into retreat. George Bush used the 9/11 attack as the pretext to launch the “War on Terror” and the occupations of Afghanistan and Iraq. This temporarily and partially helped to overcome the Vietnam Syndrome but the occupation of Iraq has led to a full scale disaster for U.S. policy, now spawning the new conflict with ISIS. Bush faced a sizable anti-war movement but, with fewer “boots on the ground”, Obama has pursued the same aims with less opposition.

But there is increasing resistance to the war being waged on working people and people of color here at home. This will inevitably lead to a greater understanding of the need to oppose U.S. intervention abroad which serves the interests of the corporate elite. Just as in the 1960s, what is needed is the international solidarity of working people fighting to end the domination of the planet by capitalism. The heroic resistance of the Vietnamese people and the mass movement against the war inside the U.S. remain a shining inspiration for this generation.

Deep Crisis Within U.S. Society

by Tom Crean

In 1975, as Saigon fell to the NLF, the US was in the middle of the most profound political, social and economic crisis it had faced since World War II. There were a number of elements comparable to what we have seen in recent years.

Beginning in 1973, the US experienced a sharp economic downturn which marked the end of the huge postwar economic expansion. By May 1975, official unemployment had reached 9%. The ruling elite were unsure of how to respond to this crisis.

All the institutions of American capitalism increasingly came into question. This process culminated in the constitutional crisis caused by the Watergate break-in. In August 1974, Richard Nixon, facing the threat of Congressional impeachment, was forced to resign because of Watergate.

But the most important feature of the situation was the development of a whole series of mass struggles that pointed in the direction of fundamental change. Besides the mass movement against the war, society had been rocked by a powerful movement for civil rights and black liberation which also helped spur movements for women’s liberation and gay liberation.

There was an enormous radicalization of young people who were inspired by revolutionary movements against colonialism and capitalism around the world. Hundreds of thousands considered themselves socialists. In 1968 there was a month-long general strike by workers in France, followed by Italy’s “hot autumn” in 1969 and the Portuguese Revolution of 1974.

The U.S. working class had not drawn such far reaching conclusions but there was upheaval in workplaces here as well. Between the mid-60s and mid-70s there was a huge wave of class struggle. In 1974 alone, nearly 1.8 million workers were out on strike and nearly 32 million workdays were lost due to strikes! Many of these were “wildcat” strikes taken without union sanction because of the frustration of workers with their leadership for not fighting back against attacks on living standards and working conditions.

What was missing was a political force with sufficient authority to galvanize the massive discontent in the working class and throughout American society. Even an initially small multiracial workers party with a clear socialist program could have rapidly reached and led millions in this period. The key lesson for today, as we witness a new wave of social struggle, is precisely the urgency of laying the basis for an independent political party to challenge the rule of the billionaires and within that the need to build a cohesive socialist force.