This article was originally published in Issue 188 of Socialism Today, the theoretical journal of the Socialist Party of England and Wales.

Having rightfully earned her place as a leader of dissent, Arundhati Roy’s most recent polemic against injustice, Capitalism: A Ghost Story, is a sturdy demolition of the ruling classes’ sprawling edifice of lies. Setting the backdrop for her tale, Roy begins with her encounter with a visceral monument to corporate predation: the home of India’s richest man, Mukesh Ambani. Housing some 600 servants, Roy was especially astounded by Ambani’s surreal and very revealing garden: “Nothing had prepared me for the vertical lawn – a soaring, 27-storey high wall of grass attached to a vast metal grid. The grass was dry in patches; bits had fallen off in neat rectangles. Clearly, Trickledown hadn’t worked”.

‘Gush-Up’, she adds, does benefit the super-rich who continue to own India: not unlike the dark days of British imperialism. Supported by 200,000 paramilitaries, government-backed vigilante militias murder the poor throughout central India. Here, committing atrocities with legal impunity, such brutality has “succeeded only in strengthening the resistance and swelling the ranks of the Maoist guerrilla army”, writes Roy. Yet she is clear that force alone has never been enough to silence the poor. This leads her onto a close examination of the ideological means by which our rulers attempt to dominate and pacify our class’s aspirations.

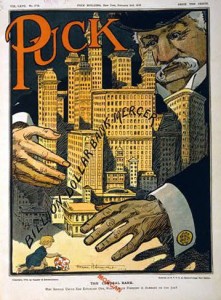

The principal target of Roy’s exposé revolves around the ruling class’s promotion of the murky politics of corporate philanthropy. She provides a brief history of the largesse of America’s robber barons of old. And Roy traces the capitalist elite’s incorporation of civil resistance back to the U.S. in the “early twentieth century when, kitted out legally in the form of endowed foundations, corporate philanthropy began to replace missionary activity as capitalism’s (and imperialism’s) road-opening and systems maintenance patrol”.

The principal target of Roy’s exposé revolves around the ruling class’s promotion of the murky politics of corporate philanthropy. She provides a brief history of the largesse of America’s robber barons of old. And Roy traces the capitalist elite’s incorporation of civil resistance back to the U.S. in the “early twentieth century when, kitted out legally in the form of endowed foundations, corporate philanthropy began to replace missionary activity as capitalism’s (and imperialism’s) road-opening and systems maintenance patrol”.

One of the first books referenced by Roy which scrutinized the negative repercussions of liberal philanthropy – focusing on the then big three foundations: the Carnegie Corporation, and the Rockefeller and Ford foundations – was Robert Arnove’s edited collection, Philanthropy and Cultural Imperialism: The Foundations at Home and Abroad (1980). The other primary source used by Roy is Joan Roelof’s overview, Foundations and Public Policy: The Mask of Pluralism (2003), a study of the rise of liberal philanthropy.

Since the heady days of the big three, the position of the world’s most powerful source of philanthropy is now held by the Gates Foundation, although the other foundations still exert much influence. “Non-taxpaying legal entities”, Roy explains, “with massive resources and an almost unlimited brief – wholly unaccountable, wholly non-transparent – what better way to parlay economic wealth into political, social, and cultural capital, to turn money into power?”

Early Carnegie interventions into the labour movement that demonstrate the utility of such philanthropy to the ruling class include the formation of the National Civic Federation (NCF) in 1900. This promoted welfare schemes (along with divisive propaganda) in an attempt to make the demands of radical trade unionists redundant. The notorious Samuel Gompers, the right-wing and first president (1886) of the American Federation of Labour, was the NCF’s founding vice-president.

In the U.S., ruling-class foundations were the guiding force behind much capitalist strategizing. For example, they created the Council on Foreign Relations in 1924. Today, it claims to be “the most powerful foreign policy pressure group in the world”. They support militaristic think-tanks like the RAND Corporation. They played a central role in creating hubs for liberal intellectuals, like the Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions (formed in 1959), “whose brief was to wage the cold war intelligently, without the McCarthyite excesses”.

Other endeavours for which the big three were intimately entwined included facilitating the overthrow of democratic governments, such as the socialist government led by Salvador Allende in Chile, 1970-73. The foundations not only supported the Milton Friedman-ite economists, known as the ‘Chicago Boys’, who ended up advising Pinochet’s military regime, they also aided the left-leaning (but far from radical) economists based at the University of Chile – the ‘dependistas’ – in Eduardo Frei’s administration (1964-70). But when Allende was elected in 1970 the Ford Foundation recognised the need for a more coercive intervention into Chile to protect US capitalism’s interests. The foundation abruptly cut off all funding for the dependistas while, in stark opposition, the Catholic University’s Chicago Boys continued to be well remunerated. The neo-liberal economists received foundation funding for four years after the military coup.

Roy relates this outrageous intervention back to India, by introducing the Rockefeller Foundation’s role in founding (1957) the Ramon Magsaysay Prize for community leaders in Asia. “It was named after Ramon Magsaysay, president of the Philippines, a crucial ally in the U.S. campaign against communism in Southeast Asia”. The first Magsaysay prize was awarded to Mahatma Gandhi’s spiritual heir, Vinoba Bhave, whose bhoodan movement’s emphasis on moderation and class conciliation was formulated in response to the activism of more radical adherents of Gandhism.

More recently, the prize has been relaunched by the Ford Foundation, grandly renamed the Ramon Magsaysay Emergent Leadership Award. Roy points out how three recipients of this award for ‘acceptable activism’ played central roles in ‘spearheading’ Anna Hazare’s so-called anti-corruption movement. Hazare, who himself won the prize – and one from the World Bank, for ‘outstanding public service’ – cloaks his elitist activism with Gandhian rhetoric. His capital-friendly anti-corruption movement culminated in calling for a new law to be passed (in the Jan Lokpal Bill) which Roy says was “elitist, and dangerous”. Needless to say, Hazare’s movement “didn’t breathe a word against privatisation, corporate power, or [neo-liberal] economic ‘reforms’.”

The promotion of such non-threatening movements by corporate elites is not unusual, hence the ruling-classes’ active promotion of pacifism for the masses, thereby maintaining a monopoly on violence. Gandhi is a good example of such elite-sanctioned activism. Leon Trotsky, writing to Indian workers in 1939, was blunt in his assessment of Gandhi as a “fake leader and a false prophet”, highlighting his role, first and foremost, in representing the interests of the Indian bourgeoisie. Although Roy’s scathing criticisms of Gandhi are not mentioned in her latest book, it is worth noting that her analysis of Gandhi’s role is not based upon class. Instead, Roy has been influenced by the writings of anti-caste activist, BR Ambedkar (1891-1956), who Roy says was equally critical of socialists as of the Gandhians.

To be fair, Roy has good reason to be upset with Indian ‘Marxists’, having grown up in Kerala, a state whose politicians have been dominated by Communists in the Stalinist tradition (formerly linked to the Soviet Union) for decades. On the question of caste, for instance, the communist parties (CPI and CPI-M) were incapable of waging an effective struggle. As T.U. Senan wrote in Socialism Today recently: “The communist parties in India, despite having a mass base, were never able to wage a class-based opposition in such a way that would also express caste anger, due to their continuous collaboration with the oppressing caste. The partial land reforms which were implemented under Communist Party rule in Bengal or Kerala did have some impact on caste relations, but their effects were limited in many ways as the majority of oppressed-caste people remained landless”. (Caste-Based Oppression and the Class Struggle, No.184, December 2014)

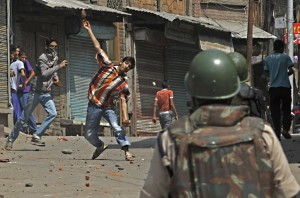

In the face of such serious setbacks, however, Roy recognises that not all is lost. Referring to the ongoing resistance in Kashmir, she writes: “Ordinary people armed with nothing but their fury have risen up against the Indian security forces”. Despite some serious flaws in her analysis, Roy does not completely ignore the role of Marxist ideas in the caste and class struggle, quoting Marx and Engels’ Communist Manifesto a couple of times in her book. She reproduces the well-known quote: “What the bourgeoisie therefore produces, above all, are its own gravediggers. Its fall and the victory of the proletariat are equally inevitable”. In the manifesto, this refers to the development of the working class, whose power of “revolutionary combination” replaced the former isolation of workers thanks to the advances made by capitalism. But Roy turns this formulation on its head by concluding: “Capitalism’s real ‘gravediggers’ may end up being its own delusional cardinals, who have turned ideology into faith”.

Ultimately, it is Roy’s aversion to Marxism, groupings and class-based politics, and her orientation towards more anarchistic ideas, that explain some of the problems in her otherwise useful political interventions. Take, for example, her headlining speech at the World Social Forum in Mumbai, 2004. The speech “contained sharp criticism of U.S. imperialism, the Indian government and all politicians conducting privatisation, including Nelson Mandela, which is rare from a speaker at this kind of event”. Yet, while she was a strong advocate of action, not just talking, “Roy recommended a ‘minimum agenda’, focused around (undefined) action against a couple of multi-national corporations”. As New Socialist Alternative (CWI India) commented at the time: “She did not give any alternative to capitalism, however, and argued against ‘ideology’ in general”.

In early 2010, again to her credit, Roy risked her life by meeting and travelling with Naxalite inspired guerrillas, fighting the government from their bases in central India’s Dandakaranya forests. Not totally uncritical of this armed resistance, Roy acknowledged that Charu Mazumdar (1918-72), the “founder and chief theoretician of the Naxalite Movement”, employed “a language so coarse as to be almost genocidal”. Yet while ignoring, or perhaps unaware of other Marxists with a progressive programme for obtaining socialism, she wrote: “… Charu Mazumdar was a visionary in much of what he wrote and said. The party he founded (and its many splinter groups) has kept the dream of revolution real and present in India. Imagine a society without that dream. For that alone, we cannot judge him too harshly”.

Roy’s approach to bringing an end to capitalist exploitation also sees her embrace the romantic idea of a tribal uprising as a viable alternative to practical Marxist strategies for social change. This can be seen from the subtitle of her second essay – The Trickledown Revolution – on her travels with the peasant-based resistance fighters: “The answer lies not in the excesses of capitalism or communism. It could well spring from our subaltern depths”. Roy concluded, with reference to the tribal warriors who have “not yet been completely colonised by that consumerist dream”: “It is necessary to concede some physical space for the survival of those who may look like the keepers of our past, but who may really be the guides to our future”.

From such misplaced conclusions it is easy to see how Roy’s recommendations for building a socialist, egalitarian future are unclear. This is most visible in the final essay of Capitalism, a short speech to the Occupy Movement in New York. On the one hand, Roy acknowledged: “We are not fighting to tinker with reforming a system that needs to be replaced”. Her first proposed reform, however, was to “end cross-ownership in businesses”. Roy’s three following demands are more radical. Nonetheless, they do not go far enough if she wants to present a revolutionary programme for social change.

This is because Arundhati Roy does not explicitly link the demands, such as prohibiting the privatisation of vital resources and public services, to the overarching goal of wresting control of the world from the capitalists and putting it in the democratic hands of the working class. Despite this, Capitalism: A Ghost Story deserves to be read widely by all who wish to bring an end to ghoulish capitalists and the needless misery that their blood-sucking tendencies inflict upon our world.