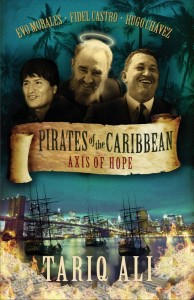

There is great interest in Hugo Chávez’s Venezuela, Evo Morales’ Bolivia, and Fidel Castro’s Cuba among workers and young people worldwide. Pirates of the Caribbean: Axis of Hope, by Tariq Ali, is informative on the processes under way in all three countries. It sometimes strikes a critical note but, unfortunately, does not draw all the necessary conclusions.

There is great interest in Hugo Chávez’s Venezuela, Evo Morales’ Bolivia, and Fidel Castro’s Cuba among workers and young people worldwide. Pirates of the Caribbean: Axis of Hope, by Tariq Ali, is informative on the processes under way in all three countries. It sometimes strikes a critical note but, unfortunately, does not draw all the necessary conclusions.

The first part is a highly-entertaining invective against all those intellectuals and former leftists who have gone over to the Washington Consensus, the capitalist neo-liberal project. They have matured, or crumbled and sold out.” In a telling phrase, Ali sums up their position: “If you can’t relearn, you won’t earn.”

The author is probably right in stating that in Latin America, unlike other continents, some of the left intelligentsia clung to part of their old socialist ideas, but not all of them.

Humberto Ortega, for instance, a senior Sandinista comandante in Nicaragua (where Sandinista Daniel Ortega was recently re-elected president), justified inequality in 1996 with a comparison of “society as a soccer stadium.”

He stated: “There’s a hierarchy. 100,000 people can squeeze into the stadium, but only 500 can sit in the boxes. No matter how much you love the people, you can’t fit them all in the boxes.” This does not bode well for the workers and poor in Nicaragua, particularly if the Sandinistas think they cannot go further than the boundary of the soccer stadium, in other words capitalist society.

Ali holds out much greater hope for Venezuela and Bolivia, and for Latin America as a whole. In so doing, he draws a comparison of the “new forces and faces… emerging in the world of Islam” with what is happening in Latin America.

He says Moqtada al-Sadr in Iraq, Nasrallah in Lebanon, and Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad indicate a “radical wind.” This is an exaggeration. The movements around these figures are still trapped in what he correctly calls “communal divisions.” He urges them to adopt an “egalitarian, redistributive socio-economic strategy,” which he claims is that of Chávez and Morales.

However, the latter two figures have not yet provided a sustained alternative to neo-liberal capitalism. Ali correctly describes the movement around these figures as essentially “social-democratic.” In a recent radio discussion, he described the radical wave in Latin America and, particularly, the policies of its leaderships as having similarities to Britains Old Labor Party and the other Social Democratic parties, which previously were workers’ parties at bottom that demanded reforms.

Venezuela

There is much truth in this, and figures like Chávez undoubtedly represent a step forward compared to all the apostles of neo-liberalism in Latin America and elsewhere. Ali’s analysis of the coup attempt against Chávez in 2002 is also informative, particularly on the processes among the Venezuelan armys rank and file and the lower levels of its officer corps.

Ali writes that in the past, “[t]he only institution that [the capitalist parties] could not completely control was the army.” The masses were sympathetic to the radical officers, even attempting to join Chávezs failed 1992 coup; 60% of the country was sympathetic to them. However, the absence of an independent movement of the working class and the identification of radical officers as their savior can produce a certain dependency among the working class.

This, in turn, can affect the working class’s consciousness, with them looking towards forces other than their own strength and organization to effect change. The masses were radicalized as a result of the attempts at counter-revolution. But the Venezuelan revolution still bears the imprint of the previous period, with top-down bureaucratic features.

The author shows the limitations of Chávez’s “Bolivarianism” when he writes: “It combines continental nationalism and social democratic reforms fuelled by oil revenues.” Ali believes this is all that is possible in Latin America in general, even in its most radicalized sectors such as Venezuela.

He writes: The Bolivarians were triumphant, but cautious. They did not change the foundations of the system. This was deliberate, as Chávez explained publicly on many occasions. We were no longer in the 20th Century. This was not the epoch of proletarian revolutions, but the beginning of a process of rethinking socialism.

But surely the history of the 20th Century is that half-measures, a quarter or half of a revolution, that do not “change the foundations of the system” will inevitably lead to setbacks and defeats. There can be no successful quarter- or half-revolutions. This is true even when the capitalists do not resort to armed force to suppress the danger of revolution, as they did in Chile in 1973 or in Spain in the 1930s.

Unless a complete rupture with landlordism and capitalism is carried through, then previous gains can be systematically undermined. Wasn’t this the case in Portugal in 1974, where a failure to take power by a democratic, socialist, workers’ and peasants’ movement led to a rolling back over time of the revolution, resulting in the catastrophic Portuguese neo-liberal capitalism existing today? The same applies, only more so, to Nicaragua.

Yet Ali, who held a Trotskyist position in the past, writes that in Venezuela “[t]he transition to a different type of state has begun, but its future will rest on its ability to transform the living standards of the poor and by inaugurating the process of economic redistribution at the level of the economy.”

His timescale for this? “The next ten years will be decisive.” He seems to believe that a gradual transformation of the state and society through reforms is possible over a ten-year period! Despite the rich natural resources of Venezuela – Castro did not have such a safety net at the time of the Cuban revolution in 1959-60 – this is not a sufficient guarantor against successful counter-revolution.

Attempted Overthrow

The author gives examples, both domestic and international, of the forceful attempts to overthrow Chávez.

At this stage, even social-democratic reforms and governments who pursue this will not be tolerated by U.S. imperialism and its local Latin American allies. It is unlikely U.S. imperialism would be capable of militarily intervening against Venezuela, given its plight in Iraq. But the attempts to mobilize the forces of counter-revolution internally could prove successful if the process of change in Venezuela is stalled.

Chávez has been fortunate in the financial benefit accruing from the rise in oil prices. However, a world economic recession or slump could have the opposite effect.

After his recent resounding electoral victory, Chávez now says he plans to nationalize the country’s main energy and telecommunications companies. He spoke of achieving “socialism in the 21st Century” and indicated support for Trotsky’s ideas of permanent revolution. If Chávez keeps his promises, this would be a big step forward for the Venezuelan revolution.

However, to defeat the attempts of international and domestic counter-revolution to overthrow Chávez and the revolution, it is necessary to mobilize mass support for real socialist change.

This would involve the setting up of democratic committees of workers and the poor, as well as farmers, democratic committees in the army and the state, and a program for the socialist transformation of Venezuela, including taking over the commanding heights of the economy, which are still in the capitalists hands.

A democratic and socialist Venezuela, acting as a beacon to all the Caribbean and Latin America, is the only way out. Unfortunately, despite the useful information in this book, it does not provide a clear program for the victory of the Venezuelan revolution.

Nevertheless, it should be read by all those wanting an inside track on what is happening in Venezuela, what happened at the time of the attempted coup against Chávez, and the Bolivarians’ outlook about the future.

The fate of Venezuela, Cuba, and Bolivia is vital, not just for Latin America but for the world. We should do everything in our power to defend everything that is progressive in these movements, while raising criticism and putting forward suggestions on how Cuba’s planned economy can be saved and how the revolution in Venezuela and Bolivia can now be completed on democratic and socialist lines.