Why are we forgotten?

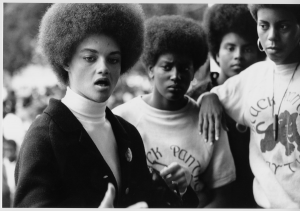

A key feature of the Black Lives Matter movement (BLM) has been the leading role played by women, particularly LGBTQ women of color within the BLM protests challenging racist and misogynistic ideas within organizations, as heads of organizations, and among those “on the front lines”. Most women of color also see the clear intersection of the BLM movement with the Fight for 15 and equality for all.

Yet within the movement, the names of Eric Garner, Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, Walter Scott, Freddie Gray and other male victims of police violence have been raised up; while female victims like Rekia Boyd, Tanisha Anderson, or Natasha McKenna are persistently overlooked. Police violence against women of color has been ignored by the corporate media, and often also met with a deafening silence by mainstream feminist organizations and activists, even when it is perpetrated against young Black women at a pool party in McKinney, TX.

All too frequently in the Black liberation struggle, we view women within traditional roles, such as mothers, wives, and sisters of male victims—and not as direct victims of state violence themselves. While women account for 20% of unarmed people of color killed by the police between 1999 and 2014, their cases rarely garner the same attention that the deaths of black men and boys do. This is not to say that we as anti-racist activists should demonize other activists for not being supportive, but rather call on the movement to recognize the invisibility of women of color, Trans persons, and those with disabilities. Exploring this phenomenon can re-center within the movement the experiences and interests of those most marginalized to ensure that we are fighting for everyone’s liberation.

Black women face double oppression in the US. They are targeted by a system built on structural racism and sexism. The corporate media continually obscures the brutal daily struggle of black women to make any kind of decent living in US society. By attempting to persuade people that we live in a post-racial meritocracy, the fault for poverty and strife is laid at the feet of the individual and not the system. They have perpetuated a false narrative that justifies the continued oppression and violence faced by black women.

Unfortunately, the sexism that is ingrained in the capitalist system often worms its way into the struggle itself. Within the Black Liberation struggle, there has been a tendency to treat Black women as secondary, and it is not new. For instance, in 1991, the leading civil rights organizations SCLC and CORE initially endorsed the nomination of noted reactionary Clarence Thomas to the Supreme Court. This was despite allegations of sexual harassment against Thomas and his clear right-wing record of being anti-black and anti-reproductive rights. This illustrated their failure to understand how Thomas’ elevation directly contradicted efforts to improve the conditions of African American women. By extension this approach undermined the entire Black struggle.

Gender and Black Liberation Politics

In the attempt to address the problems of racism in American society and grapple with the question of empowerment, questions of gender are often looked at as secondary–or worse, the role of women within struggles is wholly ignored. Women played major roles in the Montgomery bus boycott during the Civil Rights Era, but rarely held leadership positions within many of the traditional civil rights organizations like SCLC, CORE and SNCC. Partially this denial of leadership roles for women, despite their unprecedented role in the liberation struggle, was due to the denial of traditional masculine roles to African American men in larger society.

There is a whole hidden history of women fighters in the Black Liberation movement that needs to be brought out into the open. Seldom does history recall names of powerful Black Women like Vicki Garvin, the black socialist feminist that mentored Malcolm X, W.E.B Du Bois, Paul Robeson, and Claudia Jones (who all embraced feminism), among other activists in the Black Liberation struggle. Black feminists within the Black struggle fought to make feminist politics a key part of the Black Left, just as they challenged White feminists to broaden their theory to addresses racism and economic exploitation. These women’s voices are largely at odds with popular narratives of the Black freedom struggle that centered on men and located women at the margins of great social change.

The movie Selma fell victim to this tendency by completely ignoring any role besides “wife” for women like Coretta Scott King and Diane Nash, the co-founder of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and a central figure in the voting rights struggle in Selma. While the movie shows many acts of courage by women, with the exception of Coretta Scott King, women are relegated to a background role. Particularly jarring is the scene when the men arrive to Selma to get some good ol’ cooking. Of course women are only useful for cleaning, cooking, and caring for children. Ironically the storyline of Viola Liuzzo, an Italian American housewife who traveled from Detroit, Michigan to Selma, Alabama in the wake of the Bloody Sunday and subsequently murdered by Klansmen was highlighted; perhaps because the death of a white woman was considered more ‘sympathetic’.

While the Black Panther Party’s initial position was that that the role of female Panthers was to “stand behind black men”, it corrected this, and aggressively took on sexist attitudes within its ranks. Bobby Seale emphasized in his book Seize the Time that, by 1968, women represented the majority of the party. The BPP put forward the principle of valuing women in a revolutionary organization through the powerful assertions of Black women. Some of the failure to acknowledge this is due to circumstance—most members worked 20 hours per day every day, dealt with daily trauma from police, imprisonment and the complexities of being revolutionary women and often mothers. History has largely forgotten the work these women did within the more than forty BPP community survival programs. They challenged gender bias within and outside the organization, as well as sparking internal debates that went public like Huey Newton’s 1970 speech, “Women’s Liberation and Gay Liberation Struggle,” in which he encouraged women to take on leadership roles.

Capitalist society is based on the heterosexual nuclear family, in which the husband is the breadwinner while the wife is responsible for housework and child-rearing. The vision for ideal gender roles within and without the Black liberation struggle developed against this backdrop. Even as gender roles are themselves challenged by the civil rights, LGBTQ, and women’s movements, there is often a tendency to favor the extension of democratic rights to women within the limits of the economic, political and legal system of capitalism. As a movement, we need to articulate new ideals of gender.

Feminism and Gender Norms

The capitalist class structure requires racial oppression alongside sexual and class oppression. Black people share oppression with one another, but what they share as racial oppression is differentiated along class and gender lines. Within sections the BLM struggle, men are sometimes seen as the protectors of black women and black women as the guardians of our culture, and granted an honored place. Historically, we saw a particularly reactionary example of this in Elijah Muhammad’s “Message to the Blackman” in which he asserted that the first step in self-knowledge is the “control and the protection of our own women”. More recently, in the Million Man March, women were told by the organizers to stay home. The march was supported by a wide spectrum of the African-American community, but it was only due to criticism from progressive voices that march leaders modified their stand on gender, and the widows of MLK, Medgar Evers, and Malcolm X were asked to “represent” women in the march—and only as spouses of great men.

The reason that some overtly patriarchal language can be seductive to some in the movement – albeit mostly to Black heterosexual men– is because it can be seen as a way to rectify another past injustice: the denial of fragility to black women. As both laborers and slaves, Black women were historically seen as more tolerant of pain than white women while also being more ‘wily’ and needing to be brutalized into submission. This strange redress takes form in the movement when men call out for women to move to the back of the protest lines as cops step forward in riot gear.

By placing the explanation of the positions of Black women within the context of the capitalist structure, we can understand why Black women, especially those in the LGBTQ community, suffer lower life expectancy (Black men live 5.4 years less than white men; black women 3.8 years less than white women—and the differences only increases when class and educational attainment are included .) Black women are more likely to encounter the police, suffer disproportionately from poverty (28% of Blacks are below the poverty line compared to 10% of whites ), and are generally invisible to their white peers. The narrative created by the ruling class for Blacks in general has been one of laziness, violence, and criminality, and therefore they are deserving of their poverty. Racism and misogyny as a social practice are reproduced throughout capitalist society by police and judicial practices and laws, the allocation of public welfare and services, the media, and religion and education systems, thus normalizing and depoliticizing oppression within society.

Poor Black women are portrayed by those who prioritize funding for the judicial system over the pittance of welfare and education benefits as living extravagant lifestyles while raising future criminals. Manning Marable succinctly described this in ‘How Capitalism underdeveloped Black America.’ “The super exploitation of black women became a permanent feature in American social and economic life, because sisters were assaulted simultaneously as workers, as Blacks and as women.”

Black women are disproportionately poor, compared to other sections of society, experience extreme levels of violence, both in private with partner abuse and in public like with their incarceration for ‘crimes’ related to poverty. For example the impact of Hurricane Katrina—though the wide spread devastation displaced thousands of people of different races and classes—disproportionately fell on the lowest classes. Many of those who did not have the resources to evacuate were forced to seek refuge in the Super Dome and Convention Center, providing a stark example of poor and working class Black women are trapped in systems of poverty, racism, and state violence. In the weeks it took to rescue people in New Orleans, hurricane victims were denied national sympathy, and characterized as looters, criminals, and neglectful parents for not leaving before the storm hit. While people were desperately searching abandoned stores for baby formula, water and diapers, the televised media was showing a man stealing a television set. Barbara Bush even ignorantly described the conditions in the AstroDome, being used as a shelter in Houston, as being better than what people had at home.

Why Are Black Women Forgotten?

Are Black women who are victims of police brutality ignored because they are not the perfect victims? Dominant racial and class ideologies play a part in defining who is considered a ‘victim.’ This was the case with Claudette Colvin. On March 2, 1955, nine months before Rosa Parks, Colvin, a Black girl active in her local NAACP’s youth council, took a heroic nonviolent stand against bus segregation in Alabama. But the Civil Rights leaders deliberately chose Parks and not Clark as the spark to mobilize the movement around. Though civil rights activists had long wanted to wage a campaign against segregation on public transit, they passed over Claudette because she was 15, poor, pregnant, and dark skinned. Parks’ subsequent planned act of civil disobedience made her one of the most recognizable and admired Black victims of white racism of the 20th century because as Colvin said in an interview on NPR, “She fit that profile.” This was part of a media strategy to ‘pull at white people’s heart strings.’ And though Rosa Parks was given the spotlight, the part that the media really hides is determined and heroic struggle by ordinary men and women in the streets, which was decisive in defeating segregation on the Montgomery buses and Jim Crow in the South as a whole.

This selection of ‘appropriate’ victims continues today. In the 2012 summer of violence in Chicago, where in one weekend at least 40 people were shot, Hadiya Pendleton, 15, an honor student at Chicago’s Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. College Preparatory High School and a majorette in the marching band that performed at President Obama’s inauguration, became the face of the violence. She represented success in school and therefore was worthy of being mourned. Her death is a tragedy, but hundreds of Black women are dying and not even making the bottom of the screen news ticker on the 24-hour news cycle. After the social media storm around the pool party incident in McKinney, TX, Fox News anchor Megan Kelly made sure to point out that Dajerria Becton, the 15 year old victim of extreme police misconduct, was “no angel” herself as a way to undermine her victimhood.

Black women have been among the most prominent victims of the ruling class’ attempts to increase its profits through cuts to social services, wages, the public sector, and equality programs under neoliberalism. In 1996 the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act became law and dismantled the 61-year-old program of federally guaranteed Aid to Families with Dependent Children, or what is common referred to as welfare. The debate surrounding welfare reform was dominated primarily by white male politicians and journalists and focused predominantly on Black women and their families living in poverty.

The accusation that poverty is the result of the individuals’ failings of single mothers to care for their families has shaped the debates about welfare. Black Feminist writer, Patricia Collins writes, “From the mammies, Jezebels and breeder women of slavery to the smiling Aunt Jemimas on pancake mix boxes, ubiquitous Black prostitutes and ever present welfare mothers of contemporary popular culture, the nexus of negative stereotypical images applied to African-American women has been fundamental to Black women’s oppression.”

As the most narrowly racist stereotypes have significantly declined in popular culture, what replaced them is a limited number of high profile “successful” black women who do not threaten ruling class interests and who promote the idea that US society is meritocratic. The reality of the lives of most black women is basically non-existent in media, the movies, etc. The Right, of course, still pushes the idea that poverty is a moral failing, often mixed with coded racism that refers back to the worst stereotypes.

Meanwhile a government that claims to value ‘job creation’ over all else and promotes corporate “education reform” as the way to end poverty, slashes employment in sectors dominated by black women, namely the public sector. This partially explains why the unemployment rate of African American women more than 20 years of age continues to increase above 2012 averages whereas the unemployment rate has dropped for other groups. In the second quarter of 2013, it was 181 percent higher than that of white women.

In the wake of widespread protests in communities of color over the deaths of Black men, right-wing media pundits continue to point the finger at Blacks themselves, and especially women. “Welfare queens” and absent mothers and fathers are blamed for so-called bad behavior. It is easier to blame victims than recognize that “the whole damn system is guilty as hell.” A Maryland legislator suggested food stamps be denied to mothers whose sons protested. The classist aspects of his suggestion are obvious, but the sexist aspects more insidious. Black women are being held responsible for the supposedly bad behavior of Black men; Black women suffer greatly under the austere social service and public sector cuts continuing across the country; and Black women are being told to move to the back of the protests. Black women are not collateral damage in the war against Black men. Black women are also major targets, and the moral judgement passed on them materially affects their economic situation and overall quality of life.

So the question posed by the #SayHerName campaign is asked again: why are people not pouring into the streets when the cops murder a woman of color? Why is her victimhood not enough to move people to action? It is the sexism pervasive in capitalist society. It is a moral judgment repeatedly laid at Black women’s feet for the problems in poor neighborhoods. Capitalist structures that oppress women of color from all sides must be fought, but in the short term, we must challenge misogyny and racism both within our movements and in capitalist society. Where are the women? They are in the streets; they are dying at the hands of the police. We must support them in their fight for visibility.

For our socialist struggle to lift up the voices and experiences of working class women of color and to build a movement that represents the interests of all oppressed and exploited people, we must create demands and frame them in ways that highlight the particular economic and social oppression that they face. We demand:

- To dismantle the racist criminal justice system. No new increases to police forces or their power anywhere, and demilitarize the police!

- Elected, independent and fully funded civilian oversight boards with power to subpoena and the ability to oversee police budgets.

- Transparent reporting on police murder of civilians and prisoners alike

- An end to the War on Drugs and mass incarceration.

- Massive Federal and State funded jobs programs targeted to area with greatest poverty, including the most oppressed communities.

- $15 an hour minimum wage.

- Paid and extended paternal leave for all working women and men.

- Equality before the law for all people, regardless of sexual orientation and identity including the right to marriage, and greater protections within the work place and broader society.

These demands lift up all working people, but will be strongly felt amongst women of color as they have historically suffered greatest under a racist and patriarchal capitalist society. The Black woman’s struggle is a global one when we fight for freedom from police brutality and imprisonment and a guaranteed living wage to support our families.